Les travailleurs ont besoin de poésie plus que de pain.

La pesanteur et la grâce Simone Weil

- Ⅰ.Introduction

- Ⅱ.Premonition

- Ⅲ .Turning Points and Contradictions

- Ⅳ ouvrière and ouvrier

- Ⅴ The labourer and Poetry’ (1) Plato, ed.

- Continued in ‘Labour and Poetry (2): The Christ Edition.

Ⅰ.Introduction

Simone Weil’s life and philosophy were characterised by numerous intricate twists, as reflected in her writings, which offer a breadth of interpretations that often elude certainty as to whether she herself foresaw them. Her notebooks comprise a collection of fragmented reflections, which, after her death, were organised, edited, and published by her friends and fellow believers. Among her works, the celebrated Gravity and Grace (La pesanteur et la grâce) stands as a masterpiece, owing in no small part to the editorial contributions of Gustave Thibon.

The recurrent themes of ‘turning points’ and ‘contradictions’ in her philosophy, I argue, demonstrate a persistent consistency throughout Weil’s thought, especially in relation to her spiritual quest and profound engagement with Jesus Christ. Weil’s exploration of Jesus Christ led her to confront numerous religious and philosophical questions, which, I believe, served as a central axis that imparted coherence to her seemingly disparate transformations. Her efforts to reconcile faith with reason, and to deepen her understanding of life’s inherent suffering, demand thoughtful reflection, no matter how often one revisits them.

For me, engaging with her work remains an enduring source of profound joy.

Ⅱ.Premonition

In 1932–1933, a year before beginning her work in a factory, Simone Weil travelled to Germany to gain deeper insight into the foundations of fascism. In a letter dated 20 August, she observed that the Nazi Party had garnered support not only from the petit bourgeoisie but also from a significant number of unemployed individuals and other vulnerable groups. Although her stay in Berlin lasted just over two months, she retained vivid impressions of the city’s atmosphere. Former engineers struggled to obtain even a cold meal, yet no military personnel were visible on the streets.

At that time, Germany was grappling with widespread unemployment and severe hardship. In 1942, Weil confided in a letter to Father Perrin, with whom she shared a close relationship, expressing an inner conflict: “I know that if twenty German youths were to sing a Nazi song in unison before me at this moment, a part of my soul would instantly resonate with that of the Nazis. This is my profound vulnerability, yet it is how I exist.”

Upon her return from Germany, her analysis of the country encountered criticism from orthodox Marxists. Nevertheless, she endeavoured to support German exiles to the fullest extent possible.

Ⅲ .Turning Points and Contradictions

In his book Strength to Love, Martin Luther King Jr. draws on a quote attributed to a French philosopher, asserting that “a person who lacks a clear and prominent antithesis in their character is not strong.” However, the identity of the philosopher in question remains uncertain. King frequently invoked philosophical concepts in his speeches and writings, often referring to thinkers like Hegel to emphasise the necessity of balancing opposing forces to achieve harmony and progress. Hegel’s notion that truth emerges through the synthesis of thesis and antithesis aligns with King’s message of deriving strength and understanding through the reconciliation of differences and unity. Moreover, King observed that Jesus also preached about the fusion of opposites, as seen in his admonition: “I am sending you out like sheep among wolves,” and the instruction to “be wise as serpents and innocent as doves.” Although this teaching is undoubtedly demanding, it reflects the expectations that Jesus placed on his followers.

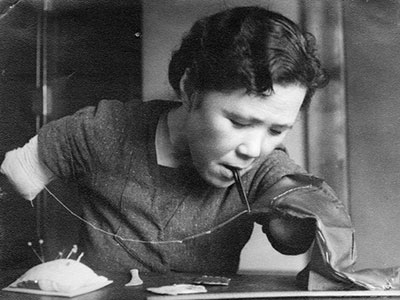

That said, Hegel was a German philosopher, which raises the question: which French philosopher might King have been referencing? Given the period, Gaston Bachelard is a plausible candidate. However, I argue that Simone Weil is equally likely. In late 1934, having resigned from her teaching post, Weil began working as a press operator in a factory, driven by a determination to confront the demands of the “real world.” Before embarking on this factory work, she had been preoccupied with the idea of creating “masterpieces” and “posthumous works.” Yet, the ideals she cherished proved difficult to sustain in the face of the harsh realities of factory life. She reflected on these experiences, recording: “I can’t help but think that interchangeable parts are like labourers. The parts seem to have more citizenship than we do,” as she entered the factory gate, displaying her numbered ID.

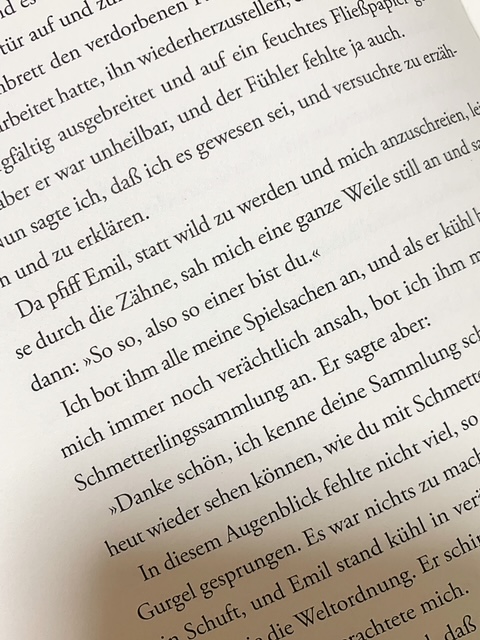

Simone Weil left behind a pivotal statement that encapsulates her philosophy: “What labourers need is not bread, but poetry.” During her time in Germany, she observed the plight of the unemployed and expressed her feelings of inadequacy to Father Perrin. The contradictions she grappled with in her philosophical and theological inquiries reflect the inherent complexity of human existence. Indeed, the notion that human essence is fundamentally complex has been explored by philosophers long before the advent of psychology. Plato’s tripartite conception of the soul and Aristotle’s examination of human nature in relation to logical virtues laid the foundation for this discourse. The exploration of human reason, emotion, and self-awareness evolved through the works of philosophers such as Descartes, Kant, and Hegel during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, expanding our understanding of the human mind. In the modern era, Freud’s scientific approach marked a critical turning point in this tradition.

Returning to Simone Weil, her assertion that “What labourers need is not bread, but poetry.” might appear paradoxical when juxtaposed with the brutal conditions of factory work. In such an environment, uncovering beauty and poetry presents a profound challenge. This tension echoes Hegel’s dialectic of thesis and antithesis. However, Weil’s philosophy, I contend, offers a distinctive perspective that requires deeper engagement with the complexities of the human spirit and psyche.

Weil also recognised that poetry could seem irrelevant to labourers, given the harshness of their daily struggles. She herself experienced the exhaustion and disillusionment intrinsic to physically demanding labour. Her philosophical explorations, particularly those rooted in biblical engagement, reflected the inner turmoil she faced. She even recorded that her distress in the factory was so overwhelming that she contemplated suicide by throwing herself into the River Seine.

Weil’s intellectual transitions and fragmented thoughts seem to form an inclusio structure, wherein statements that appear contradictory—much like the reflections of Koheleth in the Old Testament—gain coherence when examined in relation to one another. While Weil acknowledged that artistic expression had little relevance in the context of labour, she also explored the interplay between timepieces and artistry. She remarked that a clock, even when crafted with precision, functions without love, whereas a work of art requires love to resonate meaningfully. One may wonder why Weil insisted that “What labourers need is not bread, but poetry.” Even if we were to systematically outline the logical implications of her statement, conveying the mental state induced by labour at that time remains an arduous task.

I intend to unravel this challenge in my own way.

Ⅳ ouvrière and ouvrier

The direct translation of Simone Weil’s La Condition ouvrière is The Condition of the Labourer. The term ouvrière refers to female labourers, and in this work, Weil distinguishes between ouvrière and ouvrier, using the former to denote female labourers, including herself, and the latter to refer to male labourers. This distinction follows standard French grammatical conventions.

-mais jusqu’à quel point tout cela résisterait-il à la longue ? – Je ne suis pas loin de conclure que le salut de l’âme d’un ouvrier dépend d’abord de sa constitution physique.-

I am close to concluding that the salvation of a labourer’s soul depends primarily on their physical constitution.” While this idea is subjective, her use of ouvrier reflects an awareness of the collective and universal role of labourers. This distinction thus signifies both the importance of individual existence and a broader, societal perspective.

“mais jusqu’à quel point tout cela résisterait-il à la longue ? – Je ne suis pas loin de conclure que le salut de l’âme d’un ouvrier dépend d’abord de sa constitution physique. Je ne vois pas comment ceux qui ne sont pas costauds peuvent éviter de tomber dans une forme quelconque de désespoir – soûlerie, ou vagabondage, ou crime, ou débauche, ou simplement, et bien plus souvent, abrutissement – (et la religion ?). La révolte est impossible, sauf par éclairs (je veux dire même à titre de sentiment). D’abord, contre quoi ?” On est seul avec son travail, on ne pourrait se révolter que contre lui –La Condition ouvrière Simone Weil

Next, we turn to:

“But to what extent would all this endure over time? I am close to concluding that the salvation of a worker’s soul depends primarily on their physical constitution. I cannot see how those who are not robust can avoid falling into some form of despair—whether it be drunkenness, vagrancy, crime, debauchery, or simply, and far more often, stupefaction—and what of religion? Revolt is impossible, except in fleeting moments (even as a feeling). First, against what? One is alone with their work; one could only rebel against it.”

Weil’s expressive power is paradoxically revealed through her encounter with the flower of evil, exemplified by her exposure to the Bessarabo Affair (l’affaire Bessarabo) in 1920, when a man was murdered by his wife, and his body transported by train. This incident reflects the human longing for goodness, even in the midst of moral decay. Weil argues that the concept of sainthood—particularly of a female saint—is ultimately flawed. She possessed the strength to maintain opposition to idealised moral righteousness. Furthermore, her factory experience gave her first-hand insight into the lives of individuals lacking the resilience she had cultivated.

By ‘individuals lacking resilience,’ Weil refers to those without the physical and psychological endurance necessary to withstand harsh conditions. In this context, the physiological and psychological composition of the individual becomes critical in resisting social and economic pressures. For those with limited physical capacities, the risk of succumbing to despair in difficult environments increases substantially, often manifesting in addiction, social deviance, delinquency, or emotional paralysis. Moreover, their rebellions are typically reduced to brief emotional outbursts; without a clear target of opposition, the potential for meaningful change remains blocked.

(Drought -渇水)

This tension is also evident in the increasingly complex nature of contemporary poverty. The film Drought (渇水) portrays the struggles of a municipal water department worker tasked with visiting households and businesses in arrears on their water bills. When payment cannot be collected, he must carry out water shut-offs, cutting off access to water. During a summer heatwave, the residents affected by these shut-offs do not always present sympathetic cases. Some have fallen into despair, losing any sense of priority or financial planning. Others appear selfish, failing to pay their bills due to gambling addictions. In some cases, mothers in arrears prioritise their smartphones over their families’ essential needs.

In this context, the term labourers primarily refers to the water department employees. These workers often bear the brunt of public frustration, facing insults such as, “You’re just working for taxpayer money.” This conflict illustrates the tension between institutional policy and individual responsibility. Water shut-offs are implemented based on public policy, which must be applied uniformly to all users to maintain fairness and sustainability. However, these workers, despite being agents of the system, are human and must enforce these policies while facing resentment from those unable to pay. This dynamic extends to vulnerable groups, including single mothers, some of whom depend on men who leave them financially and emotionally stranded. In such cases, financial survival—not mere pleasure—drives their behaviour. Even under these circumstances, the water department employee may assist by helping families store water before shutting off their supply.

(Social Support and Institutional Constraints)

Support systems within institutions and society must continuously evolve to accommodate the needs of the vulnerable. Conversely, decisions to withdraw support on a personal level become necessary to safeguard mental health and the sustainability of shared resources. As individuals do not possess infinite emotional or material resources, boundaries must sometimes be established to preserve long-term relationships. In practice, however, people rarely have the clarity to assess these considerations when overwhelmed by hardship. This may partly explain why society often seems indifferent to individual tragedies.

Weil’s writings highlight how institutional inadequacies and injustices—such as precarious employment and insufficient social security—constrain individuals and perpetuate cycles of poverty. However, her reflections transcend the conflict between institutions and individuals by focusing on human fragility. Her philosophical inquiries explore what individuals can do and what emotions ought to be nurtured between people. Yet, the boundaries of these inquiries remain ambiguous. Weil’s search for meaning unfolds through the ‘hypothetical truths’ she articulated in her factory diaries. It is here that her concepts of ‘turns’ and ‘contradictions’ demand both lived experience and abstract understanding.

Ⅴ The labourer and Poetry’ (1) Plato, ed.

In the secondary literature surrounding Simone Weil’s renowned work “Poetry for the Labourer,” many interpretations suggest that labourers may find salvation by cultivating sensitivity and mystical richness through engaging with poetry. However, I find that this reading does not align with my understanding of her text.

First and foremost, poetry revolves around ‘intuition,’ a concept that both the author and the reader must grasp. Yet, articulating such a concept within an academic or self-help framework is exceedingly difficult. Intuition resides in a realm that language may only partially express, never fully resolving it. While language is a powerful medium for conveying human experience and emotion, it remains inherently limited.

Spiritual fulfilment and cultural experiences often transcend the boundaries of language, relying on intuitive understanding and sensitivity. This realm encompasses complexities, depth, and contradictory emotions that resist verbal expression, manifesting instead as inner transformations and profound realisations. Weil herself noted that persuading others is challenging when relying solely on impressions without concrete evidence, yet she asserted that human misery could only be expressed through impressions: “Misery is constituted solely of impressions.” Through her writing, she captures the nuanced layers of human experience that extend beyond words.

In early 20th-century France, Taylorism—a system of scientific management developed by Frederick Winslow Taylor in the United States—was widely criticised. Taylorism divided labour into smaller tasks to maximise productivity, clarifying the roles of individual workers. However, the outbreak of World War I forced France to adopt Taylorist principles to facilitate the mass production of munitions. The need for efficiency and large-scale output led to the application of task specialisation and standardisation, improving productivity but rendering the work more monotonous and exhausting. Labourers faced faster-paced tasks with reduced autonomy, and both women and children entered the workforce. After the war, France pursued economic reconstruction and industrialisation, often under difficult conditions. Many factories operated with lax safety standards, subjecting workers to long hours and constant risks of injury. Wages were low, leaving working-class families in crowded, dilapidated housing, barely able to meet their basic needs. In this environment, Weil encountered the dehumanising aspects of factory work and observed the suppression of labourers’ potential.

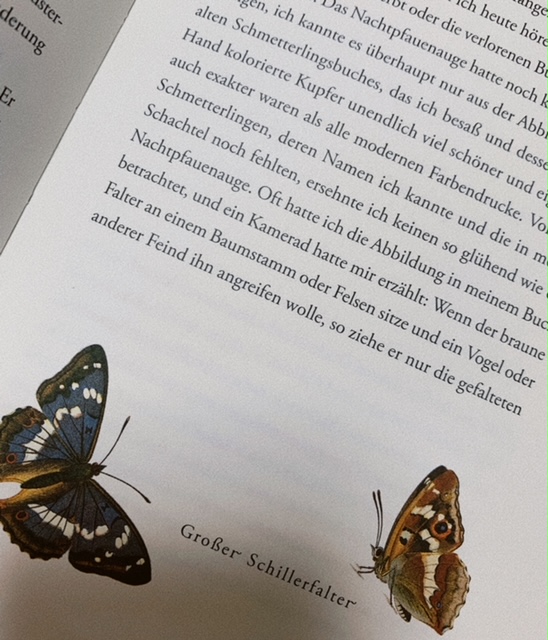

Despite its limitations, recognising the value of language remains essential for fostering empathy and holistic understanding. Beauty, sensitivity, and intuition play crucial roles in bridging the gaps left by verbal expression. At the age of 16 in 1925, Weil demonstrated an early appreciation for the symbolic nature of wisdom, observing that “Plato’s thought is most beautiful when revealed through myths.” Although she frequently referenced Plato, her interpretations of Books VI and VII of The Republic were uniquely her own.

Weil engages with Plato’s metaphor of the ‘gigantic animal’ (θηρίον μέγα) in Book VI of The Republic, in which the state and society are likened to a vast and ferocious creature. This creature possesses distinct likes and dislikes, controlled by a ‘keeper’ who knows its tendencies well. What the creature favours is deemed “good,” and what it rejects is labelled “evil.” The key insight of this metaphor is that moral judgments are dictated by the preferences of the masses, symbolised by the animal. Plato warned of the dangers posed by societies governed by such relative and arbitrary standards. Weil aligns with this critique, emphasising that social morality is merely the reflection of collective preferences—nothing more than the likes and dislikes of a gigantic animal. She contended that morality, governed by social necessity, is inherently relative and can only be transcended through divine intervention. True goodness, in her view, must be directly revealed by God to the human soul.

Weil extends her engagement with Plato by reinterpreting Book VII of The Republic through the lens of love and ethics. Using the famous allegory of the cave, she argues that “humans must turn towards the good and love beyond themselves,” advocating for ethical growth grounded in a relationship with God rather than in intellectual achievements alone. Her interpretation moves beyond Plato’s educational theories, emphasising the moral and religious dimensions of human development. In Plato’s original text, the allegory of the cave depicts the gradual progression from ignorance to knowledge. While the focus is not on love, Weil reinterprets the allegory as a meditation on the capacity to love and the impossibility of self-love, comparing the eye’s inability to see itself directly with the limits of self-love.

Even in modern times, based on my own experience, when I worked part-time as a newspaper collector in 2013, I had to visit households to collect payments. The area I was assigned to mainly consisted of elderly people living in poverty. As solicitation and collection were handled by different personnel, I often received complaints about discrepancies between what had been promised and what was delivered. When payments could not be collected, I had to visit the same households two or three times. In practice, several elderly individuals were locked into auto-renewed newspaper subscriptions, unable to read what they purchased or withdraw cash due to physical infirmities. In some instances, I found elderly women wearing adult nappies, unable to dress themselves, calling out for help. Despite their circumstances, collectors could only leave notifications of unsuccessful payment attempts. Rooms were often filled with neglect and strong odours, a testament to the overwhelming difficulties these individuals faced.

Collectors lacked the authority to cancel contracts, even when it was clear that the other party could not fulfil their obligations. Without an explicit request to cancel, I had no power to advise them otherwise. These experiences revealed the limitations of personal enlightenment and sensitivity in addressing poverty and incapacity.

Collection work, while straightforward, does not cultivate transferable skills or essential competencies. It is a task that even children could perform, offering those without experience or qualifications an opportunity to earn a modest income. However, it requires patience and a significant degree of inner resolve. In stark contrast, proficiency in my primary occupation, details of which I will withhold, directly correlates with skill development through the completion of tasks. Skills gained from collection work, however, rarely translate into other career opportunities.

It is important to acknowledge that the situations I witnessed in these homes could one day become my own reality. Life viewed through a strictly materialistic lens suggests that a severe brain injury could render me incapable of sustaining my current lifestyle. If existence is reduced to mere materiality, the erosion of human dignity becomes an ever-present risk.

It may be argued that Simone Weil’s exploration of love and God was profoundly influenced by Platonic thought, particularly by reflections on the absurdity of Socrates’ execution, which deeply affected Plato himself. Articulating such abstract concepts is no small feat, requiring the translation of intuitive insights into verbal expression. Yet, for Simone Weil, this task was indispensable.

Following the Platonic tradition, Weil believed that liberation from the tyranny of society’s ‘great beast’ could only be achieved by transcending egocentric perspectives and locating one’s value in a relationship with God. For Weil, the inherent human capacity for love manifests in turning one’s attention beyond the material world, discovering true goodness through divine connection. This pursuit, for her, embodied the Platonic “Idea.” Plato’s exploration of ideal societies and true beauty rested on the notion that material existence is transient, with real value residing in the intangible. This resonates with Weil’s yearning for spiritual depth, symbolised by her emphasis on “poetry.”