Those of us who live in this world There is no need to mourn, for I am with you. Come, let my robe Give me a cup of wine and change it.

First

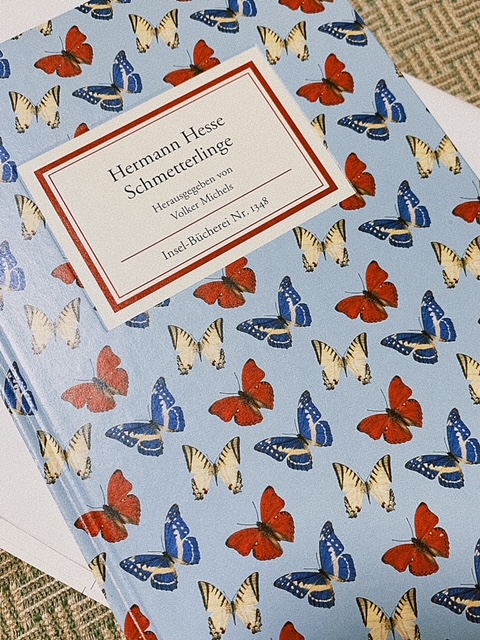

Does the poet merely dream, or does he seize the essence of truth? Is poetry a gift that fuses intuition with essence? To this day, the question remains unanswered. The biblical Psalms serve as both praise and prayer to God. Yet, in modern times, poetry has come to be regarded primarily as an expression of romance. There is a prevailing view that poetry exists to convey love, affirm existence, reflect impermanence, and give voice to the heart’s deepest emotions.

Before proceeding further, I should clarify that my understanding of Islam is limited. I will conclude this piece with my personal reflections on the film.

Second

The Old Testament cautions, “Do not take the name of the Lord in vain,” but in the Muslim world, the phrase khodā hāfez (May God bless and protect you) permeates farewells. God’s presence manifests not only in prayers but in the everyday language of greetings. This notion evokes the story of mirrors introduced to the Muslim world—mirrors that arrived shattered. These shards of glass are said to have inspired the architecture of mosques and granted poets a kind of divine intuition.

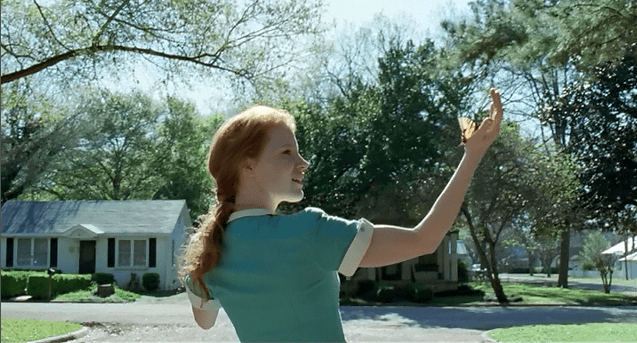

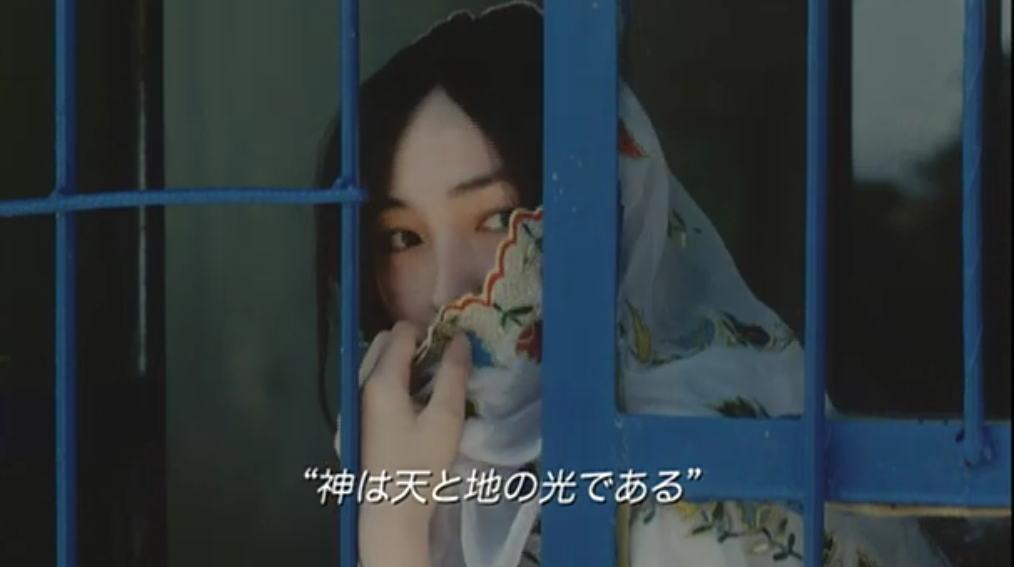

In the opening scenes of this tale, truth is likened to a mirror. This mirror, falling from heaven to earth, shatters into countless fragments. Humanity gathers the broken pieces and believes: We possess the truth. Yet the parable warns that one who gazes upon his own reflection is led astray by sin. In contrast, the one who sees a friend reflected in the shards learns the meaning of love. This philosophical image serves as the foundation for the poetic narrative that unfolds.

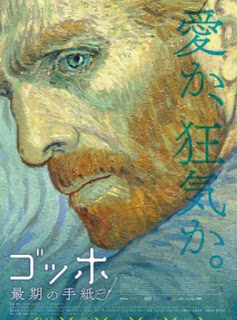

The film takes its name from Hafez, the revered 14th-century Persian poet, whose title means “guardian” or “memoriser” of the Quran. In the Muslim tradition, the recitation of sacred texts is both an art and a calling. Yet throughout history, the voice—whether poetic or divine—has possessed the power to inspire, mislead, or captivate. Just as the ancient Greek muse Calliope presided over lyric poetry, and sirens beguiled sailors, the poet’s voice carries both enlightenment and danger.

Shamseddin, the film’s protagonist, aspires to become a Hafez—a reciter of the Quran. From the age of six, he immerses himself in the study of both the Quran and astrology, straddling the lawful and the mystical. His natural gift for poetry draws admiration, but his satirical verses aimed at religious authorities provoke the ire of his teacher. Despite this, his talent earns him the title of Hafez. His duties include tutoring Nabat, the daughter of a prominent cleric (played by Kumiko Aso). Yet Hafez fears the power of Nabat’s voice, suspecting it may awaken dangerous desires within his heart. This plot mirrors a real-life anecdote of the poet Hafez, who was said to have fallen in love with a woman named Nabat.

When Nabat questions him about poetry, Hafez references the work of Sa’di, a celebrated Persian poet, instead of quoting from the Quran. Though separated by a single wall, their eyes meet, sparking a connection that does not go unnoticed. The household staff report their interaction, resulting in Hafez’s disgrace. He is stripped of his title, sentenced to fifty lashes, and cast out of the community.

Nabat is forced into marriage with another man, but she falls ill, as if her spirit has been drained. A boy with prophetic abilities claims to see fire within her, a sign that compels her husband to seek out the exiled Hafez. The husband, though constrained by societal norms, believes that only Hafez’s words can restore his wife’s health. Hafez’s reputation now tainted, he works at a job considered even less respectable than prostitution, but the husband persistently visits him, seeking a remedy. Eventually, Hafez’s words revive Nabat, and her father, moved by the miracle, agrees to forgive him—but not without a trial.

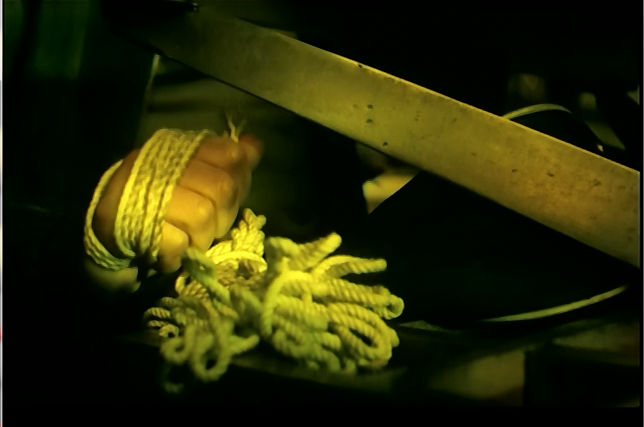

The cleric hands Hafez a mirror and imposes a daunting task: he must find seven virgins from seven villages to polish it. Failure will result in his death. However, the woman Hafez once loved is now married, making their reunion forbidden under Islamic law. The mirror symbolises love, yet the journey it demands serves as a test of forgetting it.

It is unclear whether the cleric’s challenge is a test of faith or an act of malice, but Hafez’s reputation precedes him. The villagers, forewarned, refuse to cooperate—until one maiden chooses to polish the mirror and prays for rain. Though she breaks her vow, the rain falls, and the villagers are compelled to attribute the event to divine intervention.

As word of the miracle spreads, Hafez gains a reputation as a prophet. But Nabat’s husband, obsessed with retrieving the mirror, pursues him relentlessly. Eventually, Hafez loses the mirror in one of the villages, but a guard convinces the husband to place his trust in the poet’s power. The husband, however, is accused of fabricating the prophecy and is imprisoned. Undeterred, he gives the mirror back to Hafez, who resumes his journey with it. By chance, Hafez comes across the mirror once again and is offered its return—for the price of his hair. Desperate, he shaves his head to reclaim the mirror.

In his search for the final virgin, Hafez encounters an elderly woman who, to his surprise, is a virgin. They agree to marry, but the woman dies before their vows can be exchanged. Disheartened, Hafez fears that his task is doomed. Yet unbeknownst to him, the woman he once loved remains a virgin—a fact hidden from both him and her husband.

The narrative takes a poignant turn, as the husband—perhaps driven by a misguided act of charity—sacrifices himself to aid his wife. His love, though genuine, is tainted by its incompatibility with religious law. In the end, the husband descends into madness and flees, while Nabat, still a virgin, wipes the mirror for the final time. The act is accompanied by the words Hafez once spoke to her, completing the circle of the story.

Last

When it comes to the idea of ‘sanctification,’ I chose not to contribute to the Japanese Wikipedia page on Islam. I was warned that it would likely end up as an incomplete and unhelpful entry, but it felt like the only option. I was also hesitant to offer even a partial translation. Sacred language isn’t something that can be easily expressed—and perhaps that difficulty reflects what it means to truly understand the sacred.

In Sufi tradition, the phrase ‘qaddasa Llahou Sirruhu’ (God sanctifies His secrets) suggests that saints exist in a space between life and death. However, within Islam’s strict structure, the concept of sainthood is not straightforward. While poets and reciters may speak of ‘love,’ discussions about love—whether human or divine—are not as freely explored. Films rooted in this context can’t openly depict love or rely heavily on metaphor to convey it. Even so, I found the film beautifully made, despite the many constraints it had to navigate.

Was the husband’s difficult journey rewarded in the end? The idea of ‘sanctification’ feels like something that resists simple explanation. As people of faith, we understand—like Job in the Bible or the Buddha in Eastern tradition—that suffering itself can become a form of canonisation. For us as Japanese, who are deeply familiar with the idea of life’s impermanence, the story resonates as a symbolic reflection of that truth.

What stood out most, however, was the way the characters struggled to uphold their principles. If this narrative were to take on a life of its own, it would circle back to the line at the beginning: ‘He who has seen his friend in the mirror has known love.’ In this context, the man’s suffering becomes sanctified—a divine secret. It was a love that could not be named as love, yet it was love nonetheless, recognised and carried silently. And perhaps that unspoken desire is one we all share, in some way.